1 What is Design Thinking

Wicked Problems

Design Thinking is a non-linear, iterative process which is about solving big, complex, poorly-defined problems. Problems of this nature are called “wicked problems.” Think of homelessness, climate change, hunger, poverty, the COVID-19 pandemic… These are big problems which are almost too big to comprehend, let alone solve. Rather than immediately looking for solutions, design thinking proposes that we first look more deeply into the problem and the people who are affected by it.

This way we aren’t solving the problem as we perceive it, but as others are experiencing it. Though it has applications in solving wicked problems, design thinking doesn’t need to be applied solely to the globe’s most pressing issues. It also enables understanding and defining problems with a focus on end-users’ experiences in fields including education, medicine, business, and more. It encourages organisations to focus on the people they’re creating solutions for and also enables us to tackle problems from new angles.

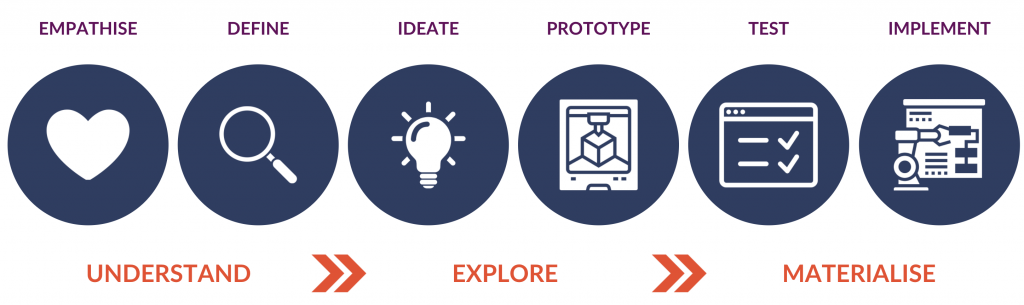

The Design Thinking Process

There are five key phases:

- Empathise

- Define

- Ideate

- Prototype

- Test

A sixth phase, implement, involves putting the newly designed solution to use.

It’s important to remember that this is not necessarily a sequential process and at any point in the design process we may need to return to empathise, ideate or prototype again.

Empathise

The best way to solve a problem is to understand what it’s like to experience that problem. Empathising enables you to learn about individuals’ needs, observe their behaviours and actions, study any other solutions which have been proposed by others, and uncover challenges. Empathy is essential to building products and experiences to solve big problems. Where a solution exists but the problem persists, we have what’s called an “empathy gap” — the disconnect between the experience businesses or organisations think they provide and the reality customers actually experience.

In practice, learning about the problems which individuals experience could involve conducting interviews, observing people and asking questions, and creating an empathy map.

Sympathy vs. Empathy

Sympathy, a word often confused with empathy, is more about one’s ability to have or show concern for the wellbeing of another, whereas to sympathise does not necessarily require one to experience in a deep way what others experience. Additionally, sympathy often involves a sense of detachment and superiority; when we sympathise, we tend to project feelings of pity and sorrow for another person.

This feeling of pity and sorrow may not only rub people the wrong way, but it is also useless in a design thinking process. In design thinking, we are concerned with understanding the people for whom we are designing solutions—for doing something that can help them. When we visit our users in their natural environments in order to learn about how they behave, or when we conduct interviews with them, we are not seeking for opportunities to react to the people; rather, we want to absorb what they are going through, and feel what they are feeling.

Author/Copyright holder: Rikke Friis Dam, Teo Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

Define

Henry Ford, founder fo the Ford motor company, allegedly once said, “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.” Whether or not he actually said this, the statement sparks considerations for design thinking. When defining a problem, we have to look beyond the obvious issue (“I need a faster horse,”) and think about the deeper root of the issue (“transportation is too slow,”). The define stage is when you assess the information gathered in the empathy phase to accurately define the problem. At the end of this phase, you should have a clearly defined problem statement which will guide your idea development.

Developing a Strong Problem Statement

A problem statement will provide a focus on the specific needs that you have uncovered and create a sense of possibility and optimism that allows team members to spark ideas in the Ideation stage, which is the next stage in the design thinking process. A good problem statement should be:

- Human-centred. This requires you to frame your problem statement according to specific users, their needs and the insights that your team has gained in the Empathise phase. The problem statement should be about the people the team is trying to help, rather than focusing on technology, monetary returns or product specifications.

- Broad enough for creative freedom. This means that the problem statement should not focus too narrowly on a specific method regarding the implementation of the solution. The problem statement should also not list technical requirements, as this would unnecessarily restrict the team and prevent them from exploring areas that might bring unexpected value and insight to the project.

- Narrow enough to make it manageable. On the other hand, a problem statement such as , “Improve the human condition,” is too broad and will likely cause team members to easily feel daunted. Problem statements should have sufficient constraints to make the project manageable.

As well as the three traits mentioned above, it also helps to begin the problem statement with a verb, such as “Create”, “Define”, and “Adapt”, to make the problem become more action-oriented.

Author/Copyright holder: Rikke Friis Dam, Teo Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

It is important to remember to employ empathy and define the problems in terms of the user rather than the designer. For example, the problem is not, “I need to increase profits of my transportation company by 50%.” Users have no interest in making you money, they want to find solutions to their problems. Therefore, the problem is, “50% of users need faster transportation options.”

Ideate

“It’s not about coming up with the ‘right’ idea, it’s about generating the broadest range of possibilities.”

– d.school, An Introduction to Design Thinking PROCESS GUIDE

Some people make the mistake of starting their design journey at the ideate stage. They may have a fantastic and innovative idea, but it does not solve a real-world need. Google Glass is an often cited example of such a failure. While Google Glass showcased exciting and cutting-edge technology, the developers neglected to take into consideration that people did not actually require this product. In fact, people so dislike wearing glasses on their faces that they will put contact lenses into their eyes on a daily basis.

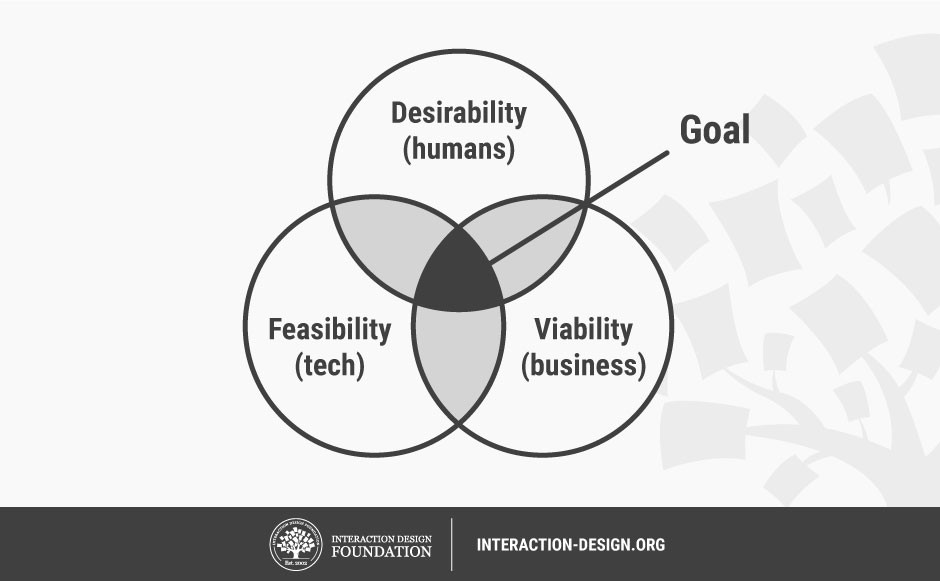

Nevertheless, this is an exciting stage of the design process. You have a clear understanding of the human needs and challenges which will drive your solution, so you can develop workable ideas. This stage requires open-mindedness and can be facilitated through brainstorming activities. Additionally, you can begin to consider which of these ideas are technologically feasible and financially viable.

Prototype

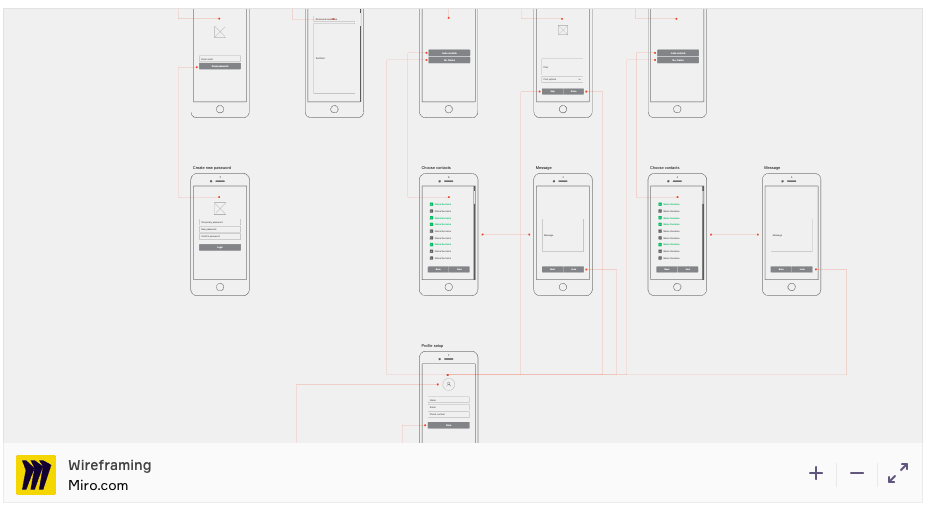

Prototyping is an essential phase before releasing a finished product. Prototypes can be created in a variety of ways, they may be low-fidelity sketches or video demonstrations, or medium-fidelity 3D-printed versions of the final product. Prototyping of your design lets you discover and repair any issues before you’ve invested too much time or money in developing, building or coding. It’s also perfectly acceptable to use prototyping as a method for determining which ideas are most feasible.

A low-fidelity prototype will be most useful in early stages of development since it can be modified quickly and easily. A higher fidelity prototype may not be created until after user testing has been carried out and perhaps even after a return to earlier stages to more clearly understand and define the problem.

Test

Testing is an ongoing process in the lifecycle of a solution. You may find that you missed some key observations and you need to return to the empathy stage before your product has even hit the market. Alternatively, as time passes, the conditions that created the initial need for your solution may change and you need to modify your approach or change the defined problem.

Testing will enable you to tweak and refine, discover anything you missed in the early stages of the design process, and create a truly innovative and successful solution.

Components of a Successful Test

- Let your users compare alternatives

Create multiple prototypes, each with a change in variables, so that your users can compare prototypes and tell you which they prefer (and which they don’t). Users often find it easier to elucidate what they like and dislike about prototypes when they can compare, rather than if there was only one to interact with. - Show, don’t tell: let your users experience the prototype

Avoid over-explaining how your prototype works, or how it is supposed to solve your user’s problems. Let the users’ experience in using the prototype speak for itself, and observe their reactions. - Ask users to talk through their experience

When users are exploring and using the prototype, ask them to tell you what they’re thinking. This may take some getting used to for most users, so it may be a good idea to chat about an unrelated topic, and then prompt them by asking them questions such as, “What are you thinking right now as you are doing this?” - Observe

Observe how your users use — either “correctly” or “incorrectly” — your prototype, and try to resist the urge to correct them when they misinterpret how it’s supposed to be used. User mistakes are valuable learning opportunities. Remember that you are testing the prototype, not the user. - Ask follow up questions

Always follow up with questions, even if you think you know what the user means. Ask questions such as, “What do you mean when you say ___?”, “How did that make you feel?”, and most importantly, “Why?”

Author/Copyright holder: Teo Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

Further Reading & Viewing

Article: This article uses a contemporary and revelatory case study to explore the relationship between three conversations in the innovation literature: Design Thinking, creativity in strategy, and the emerging area of Art Thinking. Businesses are increasingly operating in a VUCA environment where they need to design better experiences for their customers and better outcomes for their firm and the Arts are no exception. Innovation, or more correctly, growth through innovation, is a top priority for business and although there is no single, unifying blueprint for success at innovation, Design Thinking is the process that is receiving most attention and getting most traction. We review the literature on Design Thinking, showing how it teaches businesses to think with the creativity and intuition of a designer to show a deep understanding of, and have empathy with, the user. However, Design Thinking has limitations. By placing the consumer at the very heart of the innovation process, Design Thinking can often lead to more incremental, rather than radical, ideas. Now there is a new perspective emerging, Art Thinking, in which the objective is not to design a journey from the current scenario, A, to an improved position, A+. Art Thinking requires the creation of an optimal position B, and spends more time in the open-ended problem space, staking out possibilities and looking for uncontested space. This paper offers a single case study of a national arts organisation in Dublin facing an existential crisis, which used an Art Thinking approach successfully to give a much-needed shot in the arm to its commercial innovation activities.

A different approach to design and the shortcomings of design thinking, Natasha Jen: Design Thinking is Bullsh*t